At the beginning of the pandemic, when economic casualties started to emerge, fashion magazines were debated on their relevance to the “new normal,” to a society that was growing distant from luxury brands and consumerism. Yet, for years, fashion publications declined in readership, as they struggled to grasp onto revenue-generating alternatives to their high-priced print advertisement methods. Now, the question of diverse representation brings another wave of reckoning to the fashion industry.

Heeded by the BLM movement, the fashion industry is facing condemnation for their white washed reflection of society—cancellations loom large. Accountability, both individual and institutional, is required, and business leaders are stepping up to present their evidence or bare their faults in open-handed surrender (while Twitter vigilantes will upturn contradictory evidence to build their own cases). Fashion publications, with their glossy pages and elitist dispositions, are not immune.

In early June, former employees from Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue, Vanity Fair, GQ, and Glamour, spoke out about racism within the company and its magazine content. At the top of this media empire is Vogue, led by editor in chief Anna Wintour, a woman who is notorious for building a magazine founded on exclusivity.

In response to criticism for fostering a racist company culture, Wintour released an apology note to the staff at Vogue admitting, “it can’t be easy to be a Black employee at Vogue.” She continued writing, “I know Vogue has not found enough ways to elevate and give space to Black editors, writers, photographers, designers and other creators.”

As head editor for the magazine for over 30 years, she’s maintained a narrow perception of what Vogue should look like, offering few covers to Black celebrities and none to Transgender women (although Vogue Paris did in 2017). For a magazine that strives to be the prominent face of fashion, they failed to promote images and stories of diversity and adversity that reflect current social movements.

Vogue is not alone, though. Even seemingly progressive online media platforms are being called into question. ManRepeller, an online fashion blog which boasted of being a space for all women, dealt with its own reckoning among its readers and past employees who were not satisfied with founder Leandra Medine’s response to the BLM movement and the blog’s narrow portrait of women: white, rich, and husband-seeking.

Despite recent attempts by fashion publications to include Black celebrities by featuring them on social media pages, it is difficult to commend current industry moves when their pasts are so stark, still undeniably present.

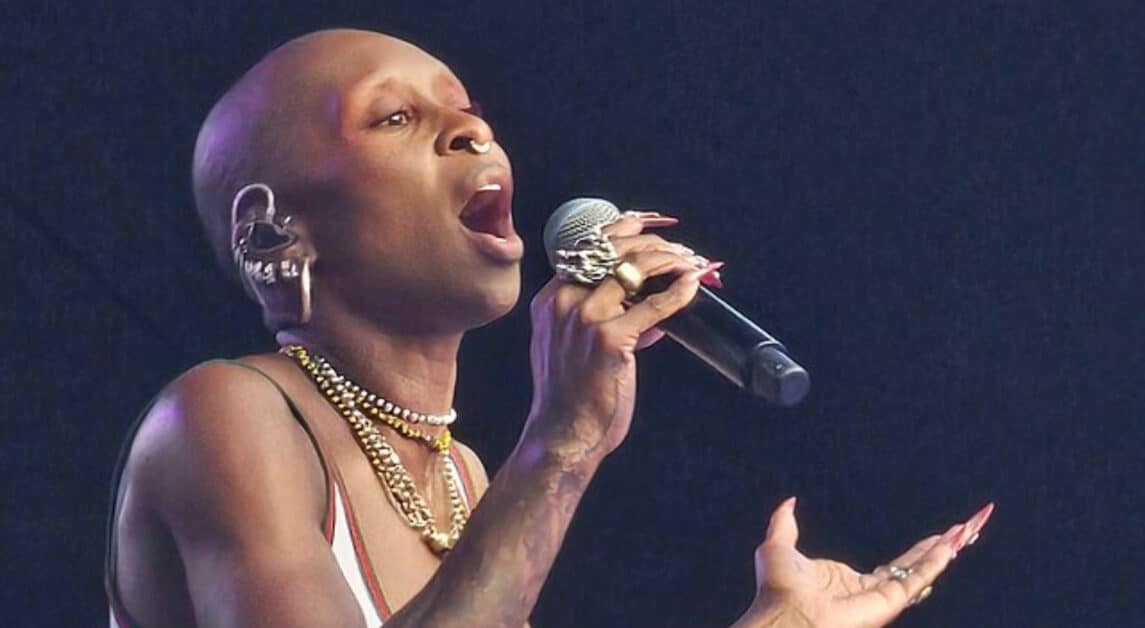

If anything, Vogue has a lot to learn from its youth-centered, and often political, alternative Teen Vogue. Lead by Lindsay Peoples Wagner, the online magazine is a remarkable example for the future of fashion publications. Not only has Wagner turned it into a popular online magazine, she’s featured young, diverse industry leaders, “people in the publication that [Wagner] felt like other publications were too scared to,” Wagner told the New York Times. This includes rapper Lil Nas X, Pose actor Indya Moore, and Euphoria actor Hunter Schafer.

Wagner and Teen Vogue are proof that change within the fashion publication industry can be done. This feat is an example of the success generated from diverse leadership and representation in the fashion industry. Recently, Wagner and Sandrine Charles launched the Black in Fashion Council, which “aims to bring diversity, inclusion, accountability to the industry,” according to Teen Vogue. Wagner is a beacon of genuity within an industry of artificial activism.

Although Wintour appointed Wagner, a Black woman, as the editor in chief of the Condé Nast publication, this decision doesn’t vindicate Wintour of her alienating actions. Wintour accepted that inclusion needed to exist at Teen Vogue, an online magazine that targets young readers, but her decision portends that diversity is only of interest to young people.

A younger generation fueled by protests, intolerance for discrimination and harmful consumerism—that is who Vogue is dependent on for its future. Yet, young Instagram users emulate the same creativity as fashion magazines, honing feeds that are just as glossy and polished as the fashion magazine spreads cultivated by previous generations. Although Vogue defined decades of images and ideals, it finds itself with no room among young consumers’ consciences today.

With employee accounts of racism at Vogue, it is even harder to pay attention to the publication now. This reckoning with representation and the BLM movement doesn’t just end once fashion publications feature more Black artists, models, and designers in their pages. Nor does it stop when they include Black editors on staff. Industry heads must be held accountable.

Adam Rapoport resigned as editor of Bon Appétit magazine, another Condé Nast publication, at the beginning of June after old photos of him emerged on social media. Although Wintour has not expressed any intentions of leaving Vogue, at Wintour’s command, the magazine now stands on shaky ground. Exclusivity is what defined Vogue, but it may also be the very thing that dismantles the 128-year-old magazine from its self-entitled pedestal.

Featured Graphic by Ally Mozeliak / Heights Editor